Written by Olga Bukhina

Когда я буду бабушкой

Годов через десяточек

Причудницей, забавницей,

Вихрь с головы до пяточек!

М. Цветаева

Written by Olga Bukhina

Когда я буду бабушкой

Годов через десяточек

Причудницей, забавницей,

Вихрь с головы до пяточек!

М. Цветаева

By Kelly Herold

The problem novel–stories with a “problem” (poverty, racism, gang warfare, sexual identity) at their core–is central to “Western” children’s and Young Adult literary traditions. From The Catcher in the Rye and Seventeenth Summer to The Chocolate War, The Outsiders, and Speak, children in the West have read stories in which children and teens confront issues and problems similar to or different from those in their own lives. Sometimes these problems are “solved” (much more likely in the American tradition) and sometimes they are not (Britain, Scandinavia, Germany), but the problem novel remains the center of Western children’s and especially Young Adult literature.

But not in Russia. And publisher Julia Zagachin (Rozovyi Zhiraf publishing house)* discusses why she is now publishing translations of Western problem novels as part of a long discussion at Snob.ru. The discussion begins with this paragraph:

Юлия Загачин давно рассказывала, что хочет издавать жесткие и правдивые книжки для детей и подростков. О настоящей жизни, которой живут наши дети в школе, в городе и в семье — о дедовщине, о коррумпированных сообществах, о тяжело больных братьях и сестрах. Скорее всего, без «хэппи-энда», но с реальными проблемами.

The discussion that follows is lively and demonstrates some of the opposition to the problem novel in Russia. One commenter writes, for example, “Хотите отнять у детей последнее – надежду и хэппи энд?…ого вы хотите вырастить? Зачерствевшие души без веры и надежды, которые не будут плакать над птичкой, потом над кошкой а потом над человеком?”

It’s a fascinating discussion about the role of books for children and young adults, so I hope you’ll head on over and read it all.

——————————–

*I do find it ethically unusual that a major magazine would “print” a statement from a publisher who is discussing soon-to-be published books. What Zagachin writes and the discussion that ensues, however, is pertinent and very interesting.

Sozialistisches Lebensgefühl: Aus dem Genre der Tragödie [1]

Irena Brežná. Die beste aller Welten. Berlin: Edition Ebersbach, 2008.

Review by Anna Schor-Tschudnowskaja (Sigmund Freud University, Vienna, Austria); Edited by Larissa Rudova, with the author’s permission

Others. Other. Otherwise: Ludmila Ulitskaia’s Children’s Book Series (1)

To date, Eksmo has published twelve books:

Reviewed by Alexandra Smith, University of Edinburgh

Social Issues in Ludmila Ulitskaia’s Children’s Book Series: Family (2)

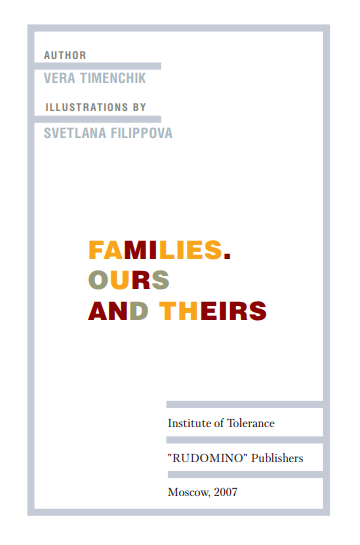

Vera Timenchik’s book, Семья у нас и у других (2006) conveys liberal sensibilities and openly discusses questions that until recently were never raised in Russian schools: xenophobia, school bullying, war in the Caucasus, ethnic intolerance, divorce, homosexual marriage, and marital age. Timenchik centers the book’s plot on two 12-year old friends: Kirill is a native Russian born in Moscow; Daut is a recent immigrant from Abkhazia, an area in the Caucasus. Kirill’s family is small and liberal; Daut’s family is, on the contrary, large and patriarchal. Yet, despite their differences, the Kirill and Daut become friends and learn to accept each other’s differences.

Vera Timenchik’s book, Семья у нас и у других (2006) conveys liberal sensibilities and openly discusses questions that until recently were never raised in Russian schools: xenophobia, school bullying, war in the Caucasus, ethnic intolerance, divorce, homosexual marriage, and marital age. Timenchik centers the book’s plot on two 12-year old friends: Kirill is a native Russian born in Moscow; Daut is a recent immigrant from Abkhazia, an area in the Caucasus. Kirill’s family is small and liberal; Daut’s family is, on the contrary, large and patriarchal. Yet, despite their differences, the Kirill and Daut become friends and learn to accept each other’s differences.

Social Issues in Ludmila Ulitskaia’s Children’s Book Series: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (3)

This just in from Larissa Rudova:

The new issue of PMLA (Vol. 126, No. 1) has a section devoted to the study of children’s literature. Larissa writes, “The section “Theories and Methodologies” (pp. 152-216) in the fresh PMLA issue (January 2011) is dedicated to children’s literature and includes such articles as, for example, “Queer Theory’s Child and Children’s Literature Studies” (Kenneth Kidd); “Comparative Children’s Literature” (Emer O’Sullivan); “Goodbye, Ghetto: Further Comparative Approaches to Children’s literature” (Kiera Vaclavik); “On Not Defining Children’s Literature” (Marah Gubar).”

In the past couple of years, two graphic novels–one American and one British–have been published about the Soviet space race. The first of these, Laika, by Nick Abadzis, was published by First Second in 2007 to great acclaim. If you haven’t read this one, I highly recommend it.

Cory Doctorow at Boing Boing calls Laika “haunting” and “sweet,” and Betsy Bird of A Fuse #8 Production (and the most well-known children’s book blogger in the U.S.) concludes that Laika, “…is an ode to dogs themselves. To the animals that we befriend and love and, ultimately, destroy. It’s also about history, humanity, and the price of being extraordinary. No one can walk away from this book and not be touched.”

(Don’t miss the comments to the Boing Boing post. In them, you will find the lyrics to a Polish children’s song about Laika and well as a reference to other artistic works about the first dog in space.)

Now a new graphic novel has come out in the U.K. (December 2010) commemorating the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s space flight. Titled Yuri’s Day: The Road to the Stars, this graphic novel aimed at a teen and adult audience is attracting some interest in Russia. Nick Dowson reports for The Moscow Times that Yuri’s Day–written by Piers Bizony, illustrated by Andrew King, and designed by Peter Hodkinson–has been well received and will soon be translated into Russian. Indeed, the authors of Yuri’s Day are responding to comments and corrections at their website for future editions of the graphic novel and for the Russian translation. It’s an interesting process, that’s for sure.

Here’s a review of Yuri’s Day: The Road to the Stars by Graham Southorn at Sky at Night Magazine (a BBC site).